Q&A: Ebbe Stub Wittrup

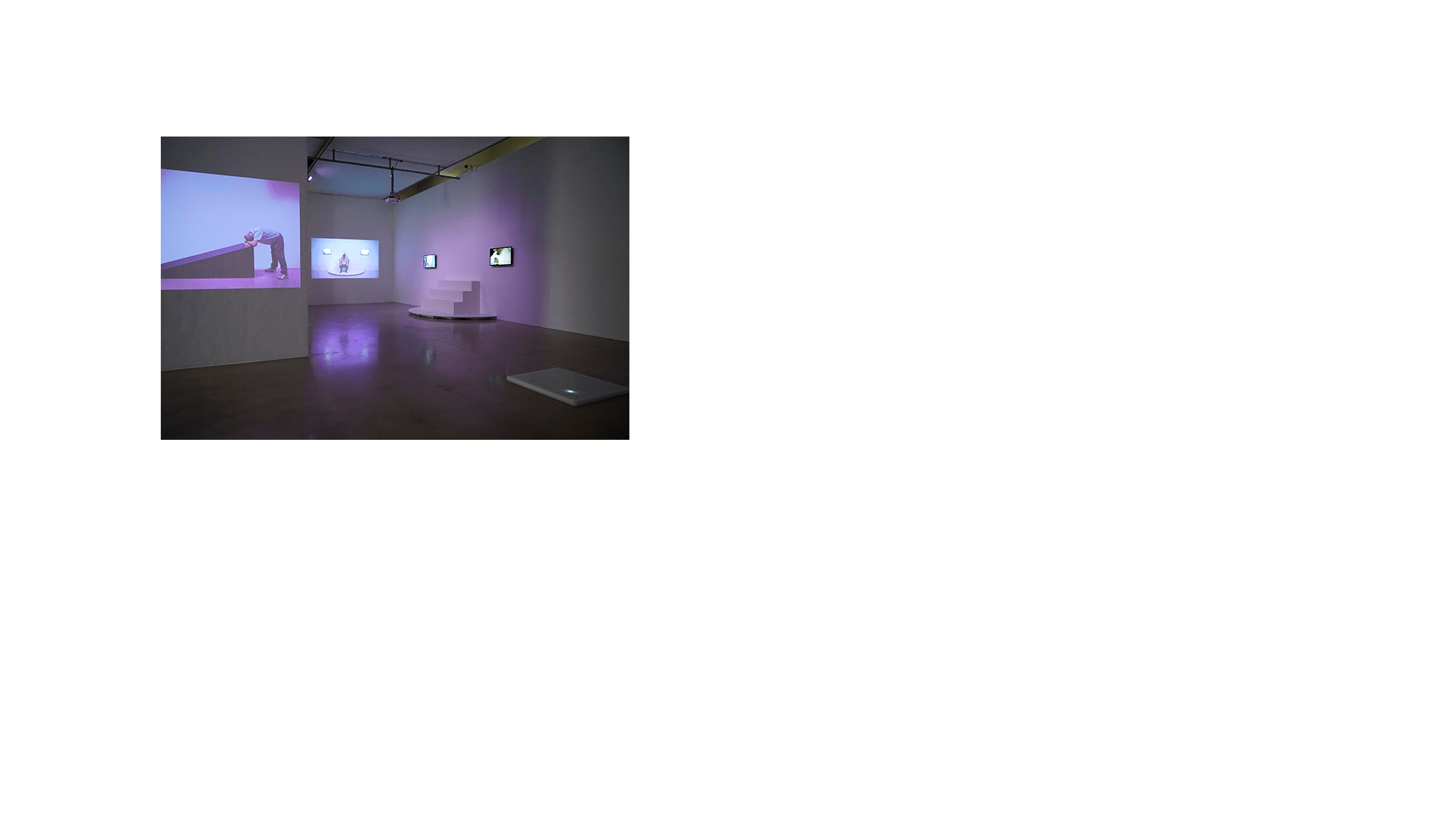

Ebbe Stub Wittrup: Botanical Drift. Wallich Herbarium. Installation view, Copenhagen Contemporary, Botanical Drift, 2020. Photo: Anders Sune Berg

-

Name:

-

Date:

-

Format:

Text

We find ourselves in grave times with environmental, climate, health, cultural and political crises weaving together. A lot is at stake; breakdowns, breakthroughs and change. Art Hub Copenhagen has initiated the program CONNECTEDNESS – Kinships and Circularity to investigate how various artistic practices and artistic research explore and build up new languages for such a powerful complexity and interweaving. It seems that we are just now realizing that everything affects and is affected by everything else, and thus it is the connections and relationships which must be investigated and explored, however difficult, unequal, symbiotic or disputing these connections may be.

One morning in September, the Danish artist Ebbe Stub Wittrup and curator Marianne Krogh met for a conversation about power, ownership and territories. Most recently, Wittrup has worked with botany, plant dyes and a Danish-Indian colonial history, and in this context he has studied the territorial connections between plants, people and geography. Wittrup has experimented with a perspective on how human and non-human bodies, cultures and territories are in constant negotiation in a mutual process of becoming; a process which breaks down a cemented cultural history and the idea of authenticity and a process with many power struggles surrounding plant definitions, stories, economies and landscapes.

The conversation took as its starting point Wittrup’s latest exhibition, Botanical Drift at Copenhagen Contemporary, where Wittrup has followed the Danish botanist Nathaniel Wallich’s collection, naming and classification of the Indian flora. A task which took place from 1807 where Wallich was sent to the then Danish colony of Serampore in India. With the exhibition, Wittrup wishes to bring into focus cultural appropriation and how the colonial materializes itself in language, plants, bodies and industries. He does this with a series of herbarium sheets, seven large banners dyed with Indian color pigments, a car of the brand Jaguar made of steel from the Indian corporation Tata Steel and with 24 different hand gestures – the Indian mythological vocabulary Mudrās – shaped in bronze and depicted by gloved hands.

Below, you can read an excerpt of the conversation between Ebbe Stub Wittrup and Marianne Krogh.

By Emmy Laura Perez Fjalland

Marianne Krogh: You told me about a textile factory in Spain which in many ways became the origin of your explorations of boundaries, territories, time, power and craftsmanship – collected in weaving, colors and patterns. Could you talk a bit about that?

Ebbe Stup Wittrup: Some years ago, I made the film Fabric of Flames* about the family driven textile factory Bujosa in Mallorca, Spain, where they weave a pattern which is called Telas de Lenguas. The pattern is specifically tied to that area, but it has wandered through centuries from Indonesia and came to Europe via the Silk Route. The pattern and the technique has migrated with hands and people and has arrived at different places in the world; with each migration, with each landscape and with each people, an imprint has been left on the pattern and the particular colors. One can recognize some of the structures in the pattern, and there are specific techniques where you tie some knots which are then dyed with plant color, and when the knots are loosened, the pattern unfolds into the thread itself and in the weaving. I became interested in the fact that modes of time exists in this; how the patterns transport themselves through different countries and different craftspeople who weave. And that they have been dyed with the plant color from plants which are found in the local landscape. It is as if both the weaving and the pattern created a space, a landscape. To see how the weavers dyed and weaved for about three weeks set off my curiosity in plant colors, cultural history and a softening of the territorial boundaries.

MK: A particular aspect of your recent work with the exhibition Botanical Drift is the power – and inequality – that emerges in connection with naming things. Could you elaborate on that?

ESW: The Indian plants already had, before Wallich named and classified them according to the Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus’ method, a long local cultural history; they appeared in mythologies, were part of the local landscapes, cultures and the local markets. Extracting and dyeing with the color pigments of the local plants was an age-old craft, created and preserved by the people who lived in exactly that place with exactly those plants surrounding them. By Wallich’s naming following Linneaus’ system of classification, a cultural appropriation took place and made possible a European colonization of the plant and its colors; an involuntary shift in ownership, which became part of the economy and maintenance of the British Empire – specifically two plants, which Wallich “discovered” (they existed prior to his discovery), are examples of this; the Indigo Plant, which has a significant blue color, and Assam tea, which is a part of Earl Grey and English Breakfast Tea, for instance.

MK: Ownership and intrusion unfold on many levels, and in many ways you yourself step into the history of naming and ‘occupying’ and present it in a new Danish context as a Danish artist. What are your reflections on this?

ESW: It has interested me to follow this Danish colonial trail, and that the idea with the plant colors and the flags (as a symbol of something territorial) was an occasion to investigate questions of linguistic appropriation, colonization, cultural heritage and the colonial roots of modern industries. I would like to contribute to creating an opportunity to talk about these things, and I would like to avoid being didactic! If I can point out and expose a problem and unfold it, I hope it will urge people to continue thinking from there. I am interested in the place where a sort of renegotiation happens, constantly, about what is what. This is where the artistic process can do something special to map out and communicate these renegotiations without being didactic, without deciding and closing and without rationalizing that which is not very logical anyways.

MK: You have said that you have wanted to look at the world with the plant as a prism. Would you like to elaborate on that and what you do?

ESW: I collect. I collect what I want to collect. There are some attractions, and I often wonder why I am interested in what I have collected. Sometimes, I suddenly see a pattern, a thread and that these collected things can have connections to each other in different ways and tell their different stories. These ‘images’ invite other investigations, dialogues and more thorough research work. It may sound like the path has a destination, a place or an art work to reach, but I have not really defined the place I am going or identified some sort of theme right away. I very much believe in keeping some things open for a very long time. In this sense, there are a lot of things I pick up and relate to where I have not been able to connect to it at first. I am attracted to things and begin to research them and then a lot of connections unfold. Some things that I have picked up previously suddenly connect to what I am working on now, and then it takes its shape at some point. I am very interested in the uncertainty of where it all ends and in trusting that it opens up and makes sense at some point.

It is like looking through a prism, to attempt to look in different directions for a long time, and that things sometimes mirror each other and sometimes do not fit together. It is about stepping out of a certain linguistic frame surrounding something; taking walks in that linguistic frame, bumping into different things and discussing it with others. In that way, one can develop a language for things that emerge along the way and which become stronger and stronger. But it is also about being able to say everything which we do not know, but which we will come to know by talking about it. It is about developing new language uses about what one investigates on the way; to always redescribe and renegotiate in conversations and collaborations with my students and my colleagues.

MK: And how does that work influence your visual arts narratives?

ESW: It helps to soften cemented cultural histories and redescribe these relationships and their territories. Visual arts can communicate these new relationships with what you could call a sensory-based fabric, where you as a spectator can get a lot of information by just sensing and experiencing. You will definitely also get something out of reading about the works, but there is a lot of information to pick up by just looking at the plant colors. As a spectator, you can sense through close observations that the colors do something and create special spatial experiences. Experiences that also reflect different cultural histories and views on nature. And perhaps these colors and fabrics open a conversation about something as intertwined as territoriality, time, and power. It is as if the things that never cement themselves continue to raise new questions. I think that is my field, and I would prefer to stay there.

* The film work Fabric of Flames was on show at Den Frie Exhibition in 2017 and was an investigation into how cultural identity, technology and traditions of craftsmanship arise and are exchanged across time and place. The work is based on footage from the Bujosa weaving mill in Mallorca.