Testing Ground : Precarious Film Practice

-

Name:

-

Date:

-

Format:

Video

In 2021 Eva la Cour, Joen Vedel, Mia Edelgart and Rasmus Brinck Pedersen took part in the Testing Ground programme at Art Hub Copenhagen. Titled Precarious Film Practice, the programme featured four live events. This page presents documentation of the process in the form of text and video.

~

PRECARIOUS FILM PRACTICE, 2021

Text with video extracts for the Art Hub Copenhagen Archive

By Joen Vedel, Mia Edelgart, Rasmus Brinck Pedersen and Eva la Cour

Eva:

Should I go first?

In the spring of 2021, we decided to devise a practical collective survey, in an attempt to give shape to some of the questions that had been on our minds for some time. What is live editing? Or, what could it be? How can you deploy mediation as artistic material? How can the actual filmic process be integrated into the way a film is produced? How can filmic work demonstrate its own working conditions? What is the purpose of film? What is a successful film? What does working in an antifilm tradition mean today? Maybe some of you can make this clearer?

Mia:

For me, one of the recurrent themes is the potential of error as a method…

Eva:

Yes, that’s important! That’s one of the reasons we decided to call our investigation Precarious Film Practice.

Joen:

For me, one important theme is the production of ‘now-time’ – something both you and I investigate in our PhD projects, albeit in different ways and based on very different material.

Eva:

For me, Precarious Film Practice served as a kind of prelude to my PhD defence (2022), in the sense that it made it possible to put spontaneous whims to the test in practice, with no sense of having to succeed, while also completing my thesis. In practical terms, Art Hub Copenhagen made their premises in Vesterbro available, along with a budget for renting technical equipment and a paying fees.

Now they’ve asked us to send some kind of documentation. I’m thinking not only of a few selected sequences of images of the visual outcome of our experiments, but also an introductory text. But since the whole point was to be part of a process together, I think it makes sense for us to try and describe and reflect on what happened together.

Rasmus:

Hm. I don’t know if I have much to say. I wasn’t there from the beginning.

Mia:

No. But you really helped shape our shared idea of what live editing is.

Eva:

I think so too, and live editing formed the basis of the Precarious Film Practice project – both in terms of the conceptualisation and execution of the actual experiments. We also had an idea of getting ‘something out of it’ together. And yes, you were part of this conspiracy.

Joen:

Yes, and we talked from the very begnning about one of our experiments being organised as a kind of workshop, and inviting you, Rasmus, to be part of it.

Rasmus:

Yes, I kind of guessed that. But still you didn’t say anything about it until the middle of the summer…

Mia:

That was a bit silly. Part of the point of an investigative project was the fact that we wanted more time for preparation than we have had on the other occasions when we deployed this practice. But I honestly think we tried to take responsibility for the fact that we were the organisers…

Eva:

And I suppose we were also very focused on kepping each session as a separate event, and maybe therefore also a little (too) hesitant vis-à-vis what would feel important to include/test further.

Joen:

But at the same time, we chose to allocate responsibility for the four different sessions we agreed on with Art Hub Copenhagen. Eva and I took responsibility for the two sessions in the spring, and Mia and Eva took responsibility for the two sessions that took place in the autumn.

Eva:

Hm. Is it worth mentioning that Precarious Film Practice was part of Art Hub Copenhagen’s Testing Ground programme? Giving us an opportunity to have some events for a very narrow audience.

Mia:

Yes, that was important. It is also important this at once introductory and reflective text we are producing is for the Testing Ground archive. Perhaps you, Eva and Joen, should start by describing the first two sessions?

Joen:

Yes, that’s a good idea. Let me start:

Precarious Film Practice #1

Joen Vedel, Eva la Cour

Group reading with invited guests. Livestream.

Joen:

For the first Precarious Film Practice event, we had invited a group of friends to take part in a reading group focusing on the ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’ by the German philosopher/critic Walter Benjamin. The reading group consisted of Marie Louise Krogh, Frida Sandström, Kirsten Dufour, Eva and me (Joen). Reading a text together was nothing new for us. We have all been part of different reading groups. But what made this reading group special was the fact that it took place in a TV studio, specially set up for the occasion in Art Hub Copenhagen’s premises, and that the reading was filmed and transmitted live on the Internet.

Eva:

That’s right. It’s important to mention that all programmes were transmitted live, and that there was a special context for this. In the spring of 2021, the corona epidemic was on the decline, but in general public events still took place with online participation…

Joen:

Yes. We invited people to the reading group to look at the importance of Walter Benjamin’s theses today, because we felt – and continue to feel – that our relationship with time and history is changing. The corona pandemic and our more or less constant presence on (a)social media have helped to change the temporal dynamics of our everyday lives. The future appears more uncertain and history has been opened up again, while the idea of the present is locked in its own logic, without any kind of horizon. We also find this feeling in Benjamin’s theses, and we were interested in understanding the complications of this. The reading group was not about understanding the theses, but about remaining curious and open in relation to them, and investigating how reading them today is relevant to us here and now.

Eva:

Should you maybe say something about the text?

Joen:

Walter Benjamin’s ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’ is regarded as one of his most important and most quoted works. He completed the text in 1940 when escaping from the Nazis. Not long afterwards, he committed suicide. The text comprises 20 theses, which in different ways criticise the perception of history as something abstract and oriented around ‘progress’ and a linear perception of time. Instead, Benjamin makes a case for a dynamic perception of time, kairos, in which the past and history are not finished, and every moment should be viewed as an opportunity for action. Together, the theses represent a kind of philosophical manifesto in the form of fragmented, dialectical images and allegories, which oscillate between the obvious and self-evident, on one hand, and the obscure and inaccessible, on the other. For that same reason, it is a good text to read in the company of others.

By transmitting our reading and discussion of Benjamin’s theses live, we wanted to create a dialogue and tension between the text and the context in which we were reading it. By using live editing equipment, we wanted to approach Benjamin’s method, and construct something out of the fragments we brought to the table, making the reading a kind of event. It was very much an experiment in using artistic space as a place, in which theory and practice – or form and content – could meet, in an attempt to understand our common reading while it was in a state of realisation.

Eva:

Benjamin wrote his ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’ as fragments, dedicated to the practice of thinking, rather than as a finished, completed work. So, what was crucial for Benjamin – and for us in this context – was the attempt to transmit an experience of historical time as it unfolds.

Rasmus:

It was a neat introduction to Precarious Film Practice #1. But what then? How was Precarious Film Practice #2 organised?

Eva:

Precarious Film Practice #2 took place exactly one week after Precarious Film Practice #1, and the layout and technical set-up of the space were actually identical. I think the only thing we changed was the colour of the oilcloth on the editing desk. It was light blue instead of red, and only Joen and I were physically present in Art Hub Copenhagen.

Precarious Film Practice #2

Joen Vedel, Eva la Cour

Editing situation without guests or studio participants. Livestream.

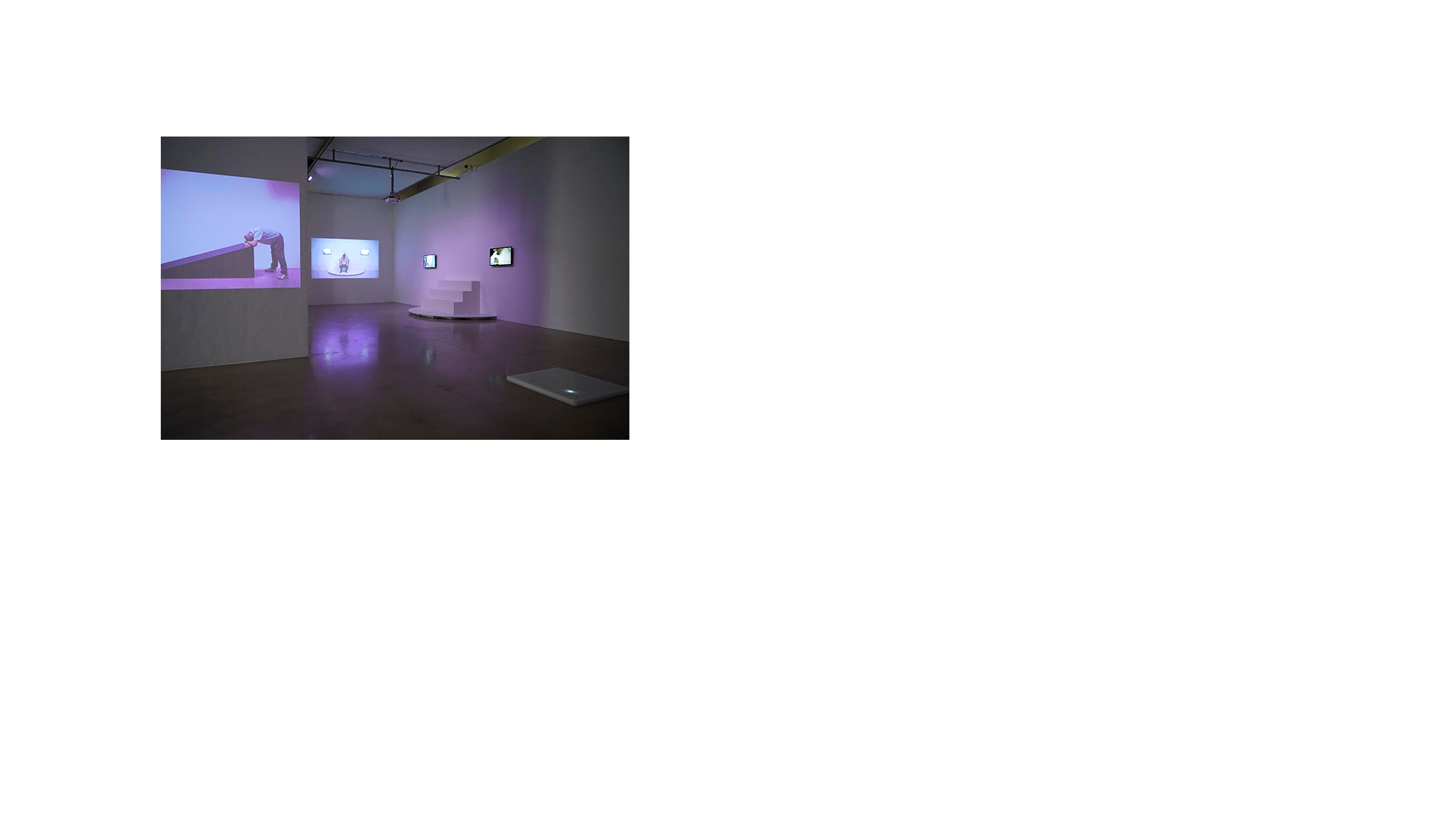

Precarious Film Practice #1 + Precarious Film Practice #2

Joen Vedel, Eva la Cour

Group reading with invited guests + Editing situation without guests or studio participants. Livestream.

Joen:

Yes. After the first event, our approach second time round was contemplative, and our attention was focused on a number of live transmissions available online: for example, via news portals, YouTube and databases.

Eva:

In practical terms, we started by introducing the live editing situation to potential viewers, by describing and explaining our setup and material. In other words, we played the archive material we had generated the previous week in the context of Precarious Film Practice #1, while it was still present in our memory and nervous system. It also formed a backdrop to a visually oriented, quite impulsive live crosscut with live-transmitted material, which we did not know and had no preconditions for working with: more specifically, a livestream from livenewsnow.com; explore.org’s live cams; a live broadcast from parliament; and a live webcam from major cities around the world. Have I forgotten anything?

Joen:

I don’t think so. Whatever, our discussion about Benjamin’s concept of time in relation to issues of the mediated/mediating gaze and coloniality, the week before, served as a kind of soundtrack that we associatively and impulsively paired with these live-broadcast image streams. The live broadcast didn’t really have a theme or direction. It was more of a visually oriented meditation.

Eva: Yes. Ha ha. Perhaps Precarious Film Practice #2 can best be described as an arbitrary, live-action reunion with the outcome of Precarious Film Training #1. Did any of you actually see it online? I don’t remember…

Mia: I saw some of it. But I think it’s fun to hear you talk about it. Partly because it’s different from what I recall. And because it’s quite different from what happened in Precarious Film Practice #3 + #4, which comprised a workshop and a street performance.

Joen:

I think it might be fun if you could describe your experience of the workshop, Rasmus.

Rasmus:

No problem. Let me start by reading from the press release and the Facebook invitation to prospective participants, both of which describe the goal of the workshop as follows: “To introduce and attempt to demystify what live editing is and can be – conceptually and technically. In addition to being a widely used method in mainstream television production, for artists live editing is a kind of machine that can give substance to airy conversations…”

“Airy conversations” were something we said we often had, as we prepared. We also talked about the fact that our workshop experiment could be called ‘Something is Taking Place’. And that it could take the form of a series of short presentations held by four different people in a makeshift studio, and in the form of a workshop with the participants both in front of and behind the camera, and with direct livestream. We also talked about how we could already pledge in advance that we were trying to approach an ‘aesthetic of potential’. I really like that. There’s something affectionate about it.

Precarious Film Practice #3 [clip 1]

Joen Vedel, Eva la Cour, Mia Edelgart, Rasmus Brink Pedersen

Workshop with 10 participants. Livestream.

More specifically, this is what took place.

Participants arrived just about on time.

The first short presentation was based on the question: Is there a direct contradiction between rebellion and watching TV? We screened clips of various interruptions of planned live broadcasts in the form of occupations, actions and fights in the live studio. Rebellion brought into the studio and then into the living room, the hermetics of the live broadcast broken up and the statement distributed. Is collaborative live editing essentially a negotiation of how we convey what’s going on in the room while it’s going on?

This was followed by a longer discussion about power and TV and network-based media. It’s interesting to watch again, because it doesn’t take long before everyone forgets to use the microphone. Sorry to the live audience. Well, then there was an introduction to the equipment, so that everyone had a chance to operate the camera and have a go at image and sound editing. The negotiation could begin.

The next presentation was titled: ‘Live Video Editing Isn’t Montage’. Here’s a little quote: The question is whether collaborative live editing can be a kind of precarious film practice that shatters the carefully managed and planned attempt of the narrative to maintain the illusion of immediacy or the illusion of simultaneity, based on the goal of training sensibility and attention collaboratively. The editing picks up speed here.

The conversation from earlier continues. There is also a long pause at some point around here. With a break sign and break jazz.

The next presentation – or actually the next text reading – was a brief reflection on the ways in which improvisation has shaped some of our own experiments with live editing. This also applies to the last feature, which was about error. All the faults and awkwardness involved in approaching the aesthetics of potential.

Precarious Film Practice #3 [clip 1]

Joen Vedel, Eva la Cour, Mia Edelgart, Rasmus Brink Pedersen

Workshop with 10 participants. Livestream.

Eva:

You can hear some of the text about improvisation, read out loud in the estract we chose for the Testing Ground archive. In the extract, you can also see an excerpt from the feature on error…

Mia:

That was a really good description.

Rasmus:

Maybe it was a bit long.

Joen:

I think it painted a really clear picture. But, Mia and Eva, maybe you should continue and talk about Precarious Film Practice #4?

Mia:

Well, I’ll have a go.

Precarious Film Practice #4

Eva la Cour, Mia Edelgart

Voxpop on the street and live editing in the studio. Livestream.

Mia:

Basically the idea was to have a go at Vox Pop as a precarious film practice method: walking on the street and questioning random by-passers. The material transmitted live was largely unpredictable, uncontrollable, full of emotion and ‘error’. What would people say? What should we answer/ask them? Whom would we meet?

In advance, Eva and I had watched Poul Martinsen’s classic TV documentary Under Uret (under the Clock) (1985), in which he portrays and interviews different people at Copenhagen Central Station about where they are going, what they do, what their lives are like and what moves them. Following in his footsteps, we chose the station as our destination with Art Hub Copenhagen both as the production studio and the point we moved from and to with the camera and microphone.

In the studio there was an editor, Maya B, with whom we had never worked before. She (live) edited between several channels: the images and the sound we transmitted from the street/railway station, and pictures from 3 cameras in the studio: one pointed down at the editing station and herself, and the others filmed screens that played an archive of various clips from examples of film history, in which Vox Pop was used. The examples included Jag är nyfiken gul by Vilgot Sjöman, Love Meetings by Pier Paolo Pasolini, Chronicle of a Summer by Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin the aforementioned Under Uret.

Eva:

Perhaps we should mention that Maya B did not know about our archive material and its timing. She edited for two hours and really had her work cut out for her, constantly having to work with what was available at any one moment.

Mia:

Yes. Nor did it make it any easier that our questions on the street were very open: for example, “What would you like us to ask you?” or, “What do you think it would be relevant to ask a stranger here and now?” or – referring to the canonical Chronicle of a Summer – “Are you happy? Can I ask you that?”

Eva:

Some of the first people we ran into were people involved in a local TV project, who had set up a tent in the square to facilitate conversations and information about COVID. The camera and the conversation soon became tricky here. The people we interviewed really knew their TV. It was about truth. Perhaps they also knew that we potentially disagreed with their truth, and now it was our production they were appearing in.

Mia:

Clearly, there was caution on both sides. But from there we moved on to the station, unclear about when we were ‘exhibiting’ people, what subject we should air, while also wanting to represent a wide range of people. The street was full of people struggling to survive from day to day, but also full of people may who have been living roughly as they wanted. The microphone and the camera were constantly pointing back at ourselves, at our own positions and identities.

Eva:

Many people did not want to be interviewed, busily or shyly wafting the microphone away, but about 50% of them were happy for us to ask them something.

Mia:

Yes. Our task was to use the equipment to establish unforeseen meetings and talk about something we couldn’t know. We ended up in conversations about food, gentrification, about looking at people, school fatigue, illness, and we could have talked about everything under the sun, depending on who we stopped. Don’t you remember asking a woman if she was happy and she replied, “What! With two 10-year-old handicapped children with a mental age of 3. Don’t talk to me about happiness!” She told us that it was her own fault, that her chromosomal defect was the cause…

Eva:

Yes, I was at a loss for words, while I tried to pull myself together and ask her about it sensitively.

Mia:

Yes. Then she became more articulate and gentler. She said she was getting used to her life. Then suddenly her train arrived and she smiled and waved goodbye and you turned away, somewhat emotional, and bumped right into a tall, nosy teenager who had been in Copenhagen to buy a special cleaning agent for a special kind of white sneakers.

Eva:

Ha ha! My goodness, yes!

Mia:

I watched the live broadcast again recently – with gentler eyes. When I first saw it, I was struck by a notorious disappointment for lack of a better word. It was much more boring and abrupt than I had imagined.

Eva:

Yes, there are always two sides to live video editing: the one that’s made and the one you imagine during the process.

Mia:

Yes, that’s right. But on the other side of the meeting between the two versions, there is an exciting job of looking at what actually is. That something that is not just about what you want to do differently next time, but also about finding the potential and maybe even the poetry in what does not initially satisfy you.

Eva:

That’s really well put. What do you others think? Can we end this discussion here?

Everyone:

Yes.